News Report: Historic Victory for Takaichi Administration

Japan’s ruling coalition, led by Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, is projected to win a massive victory in the February 8th Lower House election. Exit polls suggest that the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its coalition partner, the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin), could secure up to 366 of the 465 seats, giving the ruling bloc overwhelming control over parliamentary operations.

Reports indicate that the LDP alone could win up to 328 seats, potentially marking its best result since 1996. Prime Minister Takaichi, who took office late last year, dissolved the Lower House for a snap winter election, capitalizing on her strong personal approval ratings to secure a fresh mandate.

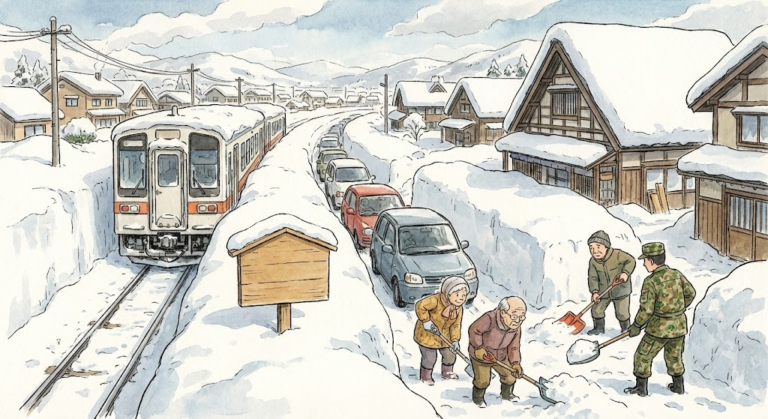

Despite heavy snowfall across the country forcing some polling stations to close early, the exit polls point to a decisive victory for the ruling coalition. The Takaichi administration ran on a platform of strengthening defense capabilities and economic security, coupled with a temporary suspension of consumption tax on food to combat inflation.

Deep Dive: Why the Opposition Failed

The 6 Miscalculations of the “Centrist Reform Alliance”

While the LDP celebrated a historic landslide, the “Centrist Reform Alliance” (CRA)—a unified front formed by the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP) and Komeito—suffered a crushing defeat.

Why did this “Centrist” experiment fail? The backdrop reveals a combination of structural defects and strategic errors.

1. Rational Math, Poor Chemistry

The concept of the CRA began with cold electoral realism. The CDP’s biggest weakness had long been a lack of organizational votes in single-seat districts. The strategy to fill this gap with Komeito’s strong nationwide network was mathematically sound, but it lacked political chemistry.

2. Policy Inconsistencies as a “Loyalty Test”

In branding themselves as “Centrist,” deep policy fissures emerged. The CDP was forced to accept policies it had long opposed—such as the acceptance of security legislation and restarting nuclear power plants—as a condition for the alliance. This acted as a “loyalty test” (Fumie) that alienated their traditional liberal base.

3. The Snap Election Highlighted Instability

Ideally, such a major policy shift requires time to explain to supporters. However, Prime Minister Takaichi’s sudden dissolution of the House did not allow for this. Rushing into the election unprepared meant internal consensus was not reached. To voters, the CRA appeared not as a party of “realistic reform,” but as a group of “indecisive opportunists.”

4. The “Division of Labor” Confusion

The candidate placement resembled a division of labor: CDP candidates for single-seat districts and Komeito candidates for Proportional Representation. This structure confused voters and failed to generate enthusiasm among independents, who saw it as a mere electoral marriage of convenience.

5. Komeito Supporters’ Nostalgia for the LDP

For Komeito, breaking away from its long-time partner, the LDP, was difficult. At the grassroots level, personal relationships with local LDP lawmakers remained strong. Consequently, a “reverse voting” phenomenon likely occurred, where supporters voted for the CRA in proportional representation but returned to the LDP for single-seat districts.

6. Defeatist Messaging

Fatal to the campaign was the weak messaging. Comments from CRA executives suggesting “a coalition with the LDP is possible” cemented the impression of a party with no will to win. To supporters, this looked like betrayal; to independents, it suggested they might as well vote for the stronger LDP.

Analysis & Conclusion

Japan Chose “Reality” Over “Ideals”

The decision made by Japanese voters was neither a dramatic revolution nor a desperate gamble. It is natural to view it as a highly pragmatic choice: abandoning the opposition’s confused new party concept and ratifying the Takaichi administration’s path, which was already in motion.

1. “Track Record” Valued Over “Adjustments” The Takaichi administration, launched last October, has made rapid moves in just a few months. Voters chose the reality of governance currently in motion over the opaque dream of reform.

2. “Anti-LDP” Is No Longer a Winning Strategy Simply “not being the LDP” is no longer enough. The “Centrist” banner lacked substance in the face of rising economic and security anxieties. Voters saw the opposition not as a “hope,” but as a “risk.”

3. The Upper House as the Final Brake While the LDP secured a massive victory, the House of Councillors (Upper House) remains as an institutional check. Even with a Lower House landslide, careful parliamentary management is essential to pass bills. Nevertheless, the strong mandate will likely accelerate the execution of Takaichi’s policies.

Summary: Japan Chose to Move Forward

This election result was an expression of the public will: a dislike for stagnation and a demand for change and decision-making. Voters have given Prime Minister Takaichi a strict mandate to produce results.

Whether this choice leads to fortune or failure depends on the future management of the administration and the watchful eyes of the public.

References

Japan’s Takaichi set for landslide election win, exit poll shows (Reuters)

Japan election: conservatives on course for victory as snow hits turnout (The Guardian)